THE SEGREGATION OF HISTORY

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma, Tate Brady was a “pioneer, entrepreneur, member of the Oklahoma Bar, politician, and early booster of Tulsa.” The Brady Heights Historic District website calls him “a pioneer Tulsa developer and entrepreneur, who was a powerful political force in the state’s early years. He was Oklahoma’s first Democratic National committeeman, and he built the Cain’s Ballroom and the now extinct Brady Hotel.” Tulsa World wrote: “Brady, a pioneer merchant, was an incorporator of the city, as well as a political leader at the time of statehood." All of these accounts exclude any direct mention of Brady’s less-than-honorable traits: his violent behavior, his attempts to segregate Tulsa, his deep involvement with the Klan and affiliated organizations, and his abuse of power. “Well, it’s political,” one employee of the Oklahoma Historical Society said, when asked about the gaps in Brady’s biography. Despite the widespread segregation of memory surrounding Brady, a rounder, more accurate portrait of the man emerges when all of the history is taken into account.THE MAKING OF COMRADE TATE

Wyatt Tate Brady was born in Forest City, Missouri, in 1870, and moved to Nevada, Missouri, when he was 12. By the time he was 17, he had taken up work at W.F. Lewis’ shoe store, where he encountered his first brush with real terror—as a victim. In the early morning hours of March 3, 1887, a customer unfamiliar to Brady entered the store. The stranger asked to see samples of shoes and offered to pay for them. Suspicious of the customer, Brady slipped his revolver from under the counter into his pocket. When Brady went to the safe for change, the stranger rushed Brady and shot at him, sending a bullet through Brady’s left ear. Brady fired a shot back, missing the robber. A disoriented Brady was then pistol-whipped and the robber made his getaway. Undeterred by the assault, Brady set out for a new frontier. Three years later, in 1890, the young bachelor headed toward the Creek Nation, Indian Territory, to make his mark as a merchant, providing goods for the established cattle trade and railroad. By Brady’s arrival, Tulsa had a cemetery, [8] a Masonic lodge, a post office, a lumberyard, and a coal mine. Five years after his arrival in Tulsa, on April 18, 1895, Brady married Rachel Cassandra Davis, who came from a prominent Claremore family. She was 1/64th Cherokee, which gave her new husband special privileges among the Cherokee tribe. [9] Together, the Bradys had four children: Ruth, Bessie, [10] Henry, and John. Three years later, January 18, 1898, Brady and other prominent businessmen signed the charter that established Tulsa as an officially incorporated city. Tate Brady was now a founding father of Tulsa. “Indian and white man, Jew and Gentile, Catholic and Protestant, we worked together side by side, and shoulder to shoulder, and under these conditions, the ‘Tulsa Spirit’ [11] was born, and has lived, and God grant that it never dies,” Brady wrote in a Tulsa Tribune article. Brady was operating a storefront by this point and preparing to expand his operation when an event occurred that would forever change Tulsa’s history. In 1901, the Red Fork oil field was discovered, which catapulted Tulsa onto the scene of world commerce. As the city began to swell with oil-minded entrepreneurs and workers, Brady saw an opportunity: the visitors needed a place to stay. In 1903, he opened the Brady Hotel, located at Archer and Main street, just a short walk from the railroad tracks. It was the first hotel in Tulsa with baths. By 1905, with the discovery of more oil in the Glenn Pool south of town, the Brady Hotel found itself with a rush of clientele. [12] With his hotel and mercantile businesses thriving, Brady began broadening his scope of influence. He lent financial support to an early paper called the Tulsa Democrat, and he began to buy and develop land near his businesses. [13] along the way, Brady became a true Tulsa booster. In March of 1905, he, along with a hundred civic leaders, a 20-piece band, and “the Indian” Will Rogers, hired a train and toured the country to promote Tulsa as a city with unbound potential. Brady’s Confederate sympathies ran deep—sympathies that would steer his actions in later life. His father, H.H. Brady, had fought as a Confederate soldier in the Civil War. By 1912, Tate Brady’s name had already appeared in Volume 20 of the Confederate Veteran. The magazine listed him as the commander of the Oklahoma Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. In 1915, Nathan Bedford Forrest, General Secretary of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, visited Tulsa. In the Confederate Veteran, Forrest wrote that he consulted with “Comrade Tate Brady,” and together they made plans for “an active campaign throughout Oklahoma.” Forrest, it should be noted, was the grandson of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a pioneering leader of the Ku Klux Klan.Nathan Bedford Forrest II, General Secretary of Sons of Confederate Veterans and a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. Click thumbnail for larger image.

THE TULSA OUTRAGE

Tulsa’s oil was an important national resource during World War I. By 1917, the city was selling a tremendous amount of Liberty Bonds, a type of war bond that helped bolster the USA’s financial position during the war. Because the war effort consumed so much oil, however, Tulsa stood to gain massive economic benefits. Any opposition to the war was viewed as a threat to personal prosperity and success. To help support the war effort, the national defense act established the state Councils of Defense. In Tulsa, the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce fulfilled that role. Its members were asked to report any seditious activities, including statements of dissent, acts of industrial sabotage, or “slackerism” (the refusal to participate in work or war). In Tulsa, this essentially put business leaders in charge of finding and reporting anything or anyone they found threatening to the war effort. No group was more hated or feared in Tulsa than the IWW. As individuals publicly opposed to the war effort, wobblies felt compelled to dampen industrial productivity by encouraging workers to strike. If such a strike were to occur, it could impact oil production and threaten the supply of oil to the military campaign. Tulsa’s economy was vulnerable to an act of worker sabotage. On August 2, 1917, a sharecropper’s uprising in southeastern Oklahoma resulted in the arrest of several hundred people. The Green Corn Rebellion, as it came to be called, essentially ended the socialist movement in Oklahoma. It also proved that anti-war sentiments had not only reached a wide level of social acceptance among working-class Oklahomans, but had escalated to the point that many were willing to take up arms in opposition to the war. Brady held a particularly strong antipathy for the Wobblies. Just a few days before the Tulsa Outrage, on November 6, 1917, Brady saw a rival hotel owner, E.L. Fox standing at the corner of Main and Brady streets. A year prior, Fox had leased an office to the IWW, unaware of the Wobblies’ mission. Their presence in the neighborhood infuriated Brady. “When are you going to move those IWW out of your building?” Brady yelled at him. “There’s no North Side Improvement Association anymore,” Fox replied, implying that Brady had no authority over Fox’s business affairs. [14] An aggravated Brady punched Fox, knocking him to the ground and beating him into the gutter. dozens of people witnessed the assault, which was reported in the Tulsa Daily World the following day. The Council of Defense had no better ally or mouthpiece than the Tulsa Daily World, Tulsa’s largest newspaper. Historian Nigel Sellars called the World “the most pro-oil industry, pro-war, racist, anti-foreigner and anti-labor paper of them all.” [15] Throughout 1917, most of the paper’s vitriol was aimed at the IWW, whom the World accused of being a German-controlled organization. In what is arguably one of the lowest points in the paper’s history, Tulsa Daily World published an editorial titled, “Get Out the Hemp.” [16]Glenn Condon, a managing editor for the World, wrote that “the first step in whipping Germany is to strangle the I.W.W.’s [sic]. Kill ’em as you would any other snake. Don’t scotch ’em; kill ’em. And kill ’em dead.” The day after the article was published, the seventeen Wobblies were convicted of a minor charge and handed to the Knights of Liberty by Tulsa’s own police. Brady was a ringleader in the kidnapping and ensuing torture in the woods west of town. Only two people in the mob were not robed—a reporter and his wife. The reporter was Glenn Condon, [17] who at the time was also serving as a member of the Council of Defense. A month after the incident, in the December issue of their magazine Tulsa Spirit, the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce included this note: “The Tulsa social event of November to attract the most national attention was the coming out party of the Knights of Liberty with about seventeen I.W.W. in the receiving line. As is usual in such social functions, a pleasant time was not had by some of those fortunate enough to be present.”Glenn Condon, Managing Editor, Tulsa Daily World. Click thumbnail for larger image.

DIXIELAND

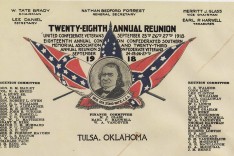

Terrible as it was, the Tulsa Outrage foreshadowed an event that would soon eclipse it in violence and notoriety. By 1918, extralegal violence, including lynchings, had spread throughout the state and had appeared to gain a quiet acceptance and collaboration among law enforcement, politicians, and business leaders. during this heated period of racial tension, Tate Brady and the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce brought the Sons of Confederate Veterans 28th Annual Reunion to town. [18] Back then, the Sons of Confederate Veterans wasn’t merely a benign Civil War re-enactment club, as it is so often portrayed in today’s media. One of its organizing principles was, and remains, “the emulation of [the Confederate veteran’s] virtues, and the perpetuation of those principles he loved.” As the largest gathering of Confederate veterans since the Civil war (more than 40,000 attended), the 1918 Tulsa convention celebrated Southern nostalgia and ideologies. Tulsa leaders banded together to raise over $100,000 to cover the cost of the event. Reunion visitors were treated to the best of Tulsa’s marvels: tours to the oil fields, free trolley tickets, and lodging with modern-day heated quarters. Although Tate Brady was the primary organizer of the reunion, its committee members included judges, ministers, and influential names that are still widely recognized in Tulsa: R. M. McFarlin, S. R. Lewis, Earl P. Harwell, Charles Page, W. A. Vandever, Eugene Lorton, and J. H. McBirney. The event was so popular that it took up several columns on the front pages of the Tulsa Daily World, which helped promote a number of other ancillary events happening across the city. While the reunion was largely received as an economic boost of Civic Pride, history won’t excuse the darker attitudes that motivated the organization and its leaders. The reunion’s figurehead, Nathan Bedford Forrest, served as the KKK’s Grand Dragon of Georgia, and an “Imperial Klokann” for the national Klan. [19] The Klan actively recruited its members from the Sons of Confederate Veterans. A few years after the convention, Forrest served as the business manager of Lanier College, the first KKK college in Alanta. “our institution will teach pure, 100 percent Americanism,” Forrest told the New York Times. The 28th annual Sons of Confederate Veterans Convention demonstrated that Tulsa’s most powerful and influential leaders at the very least tolerated—and at the most promulgated—the beliefs and biases that primed Tulsa for its most violent display of racial tension, the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Publicly, there was no dissenting voice, no expressed opposition to the Tulsa Outrage or the reunion.Many prominent Tulsans helped promote the Reunion, which was officiated by Nathan Bedford Forrest, a KKK leader. Sons of Confederate Reunion letterhead courtesy Eddie Faye Gates. Click thumbnail for larger image.

BRADY AND THE RIOT

Tate Brady’s prominence and wealth increased with each passing year. In their tenure, his retail stores sold some $5 million worth of goods (60 million in today’s dollars), and the Hotel Brady did $3 million in business. He began to invest in coal mining operations and farming interests. In the early twenties he began expanding his property holdings, spending $1 million in property acquisitions— some of which was in Greenwood. In 1920, Brady built a mansion overlooking the city and modeled it after the Arlington, Virginia, home of one of his personal heroes, General Robert E. Lee. The home contained murals of famous Civil War battle scenes favorable to the Confederacy. Brady and his wife held galas celebrating Lee’s birthday. By 1921, Brady was a recognized city leader and a tireless booster of “Tulsa Spirit,” a term he coined. Yet despite his position at the top of the town’s social circles, he managed to find time to volunteer when civic duty called. When the Tulsa Race Riot occurred on May 31, 1921, mayhem broke out in Greenwood, with buildings catching fire just two blocks from the Hotel Brady. During the early morning hours of June 1, white mobs numbering in the thousands were spotted on each major corner of the Brady district. [20] They headed eastward, invading Greenwood. Brady and a number of other white men volunteered for guard duty on the night of May 31. During his watch, Brady reported “five dead negroes.” One victim had been dragged behind a car through the business district, a rope tied around his neck. The following week Brady was appointed to the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange Commission. The Exchange, created by the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, was tasked with assessing the property damage. [21] The loss was estimated at $1.5 million. In conjunction with the City Commission, the Real Estate Exchange planned to relocate black Tulsans further north and east, and to expand the railroad’s property over the damaged lands. “We further believe that the two races being divided by an industrial section will draw more distinctive lines between them and thereby eliminate the intermingling of the lower elements of the two races,” the Exchange told the Tulsa Tribune. The Exchange then created new building requirements that made rebuilding in the area difficult. The Exchange reasoned that if residential property could be inhibited, commercial property would take its place, increasing its value by over three times its original cost. Greenwood’s property value could skyrocket, and the races could be separated. To the Exchange commission, it must have seemed like an ideal plan. Accusations of land-grabbing tormented Brady so much that he publicly issued a $1,000 reward to anyone who could prove that he benefitted from the Tulsa Race Riot. Brady, incidentally, owned rental properties that were destroyed in the riot, and tried to collect insurance on them, but did not succeed.Hear a reenactment of Tate Brady’s testimonial before an Oklahoma military tribunal.

Despite the Exchange’s efforts, Oklahoma’s Supreme Court overruled the proposed ordinances, allowing Greenwood citizens to rebuild. [22] Black Tulsans were left to rebuild their homes without any aid from the city or from insurance companies. [23]

BRADY’S CURSE

Following the riot, Klan activity increased. A large parade of Klansmen, women and youth was organized in the months following the riot. In 1923, the Klan, established as the Tulsa Benevolent Society, paid $200,000 for the construction of a large “Klavern” or gathering hall that could seat 3,000 members. Beno Hall, as it was known, was located at 503 N. Main St., on land owned by Brady. [24] Brady’s prominence in Oklahoma politics suffered a setback when Oklahoma Governor John C. Walton targeted the Klan. In August of 1923, Walton put Tulsa under martial law to investigate Klan activity. During a related Oklahoma military tribunal in September 1923, Brady admitted his membership in the Klan. [25] “I was a member of the Klan here at one time, “ Brady said, claiming he resigned his membership by October of 1922. “I have in my home the original records, some of my father’s membership in the original Klan, and I think that you [the current Klan] are a disgrace.” he didn’t like the Klan telling him how to vote, he explained. [26] Brady’s testimony hinted at a larger social predicament. Oklahoma’s Democratic Party was losing its dominance to the republicans, putting Brady, a committed democrat, in a weaker position politically. Nevertheless, he still appeared outwardly hopeful. “As I look about me during this my thirty-fourth year in Tulsa, I see locks, once raven, sprinkled with snow, and life’s fires burning low in the eyes of pioneers once bright,” Brady wrote. “As we start this new year of 1924 may the spirit of the pioneer—the spirit that built Tulsa—prevail as of yore. Cursed be he, or they, who on any pretext try to divide our citizenship and destroy this spirit.” While he saw a sunny future for Tulsa, Brady’s own situation did not appear as golden. By 1925, his considerable holdings had been reduced to about $600,000, according to a Tulsa Daily World estimation, which also suggested that he was indebted on those holdings. [27] In the spring of that year, his son John Davis Brady—a promising law student at the University of Virginia—died in a car accident. Lacking the political power he once held through both the Democratic Party and his Klan affiliations, diminished in his fortune, and aggrieved by his son’s death, Brady began to fall apart. Tulsans reported seeing him dining at his hotel alone, staring into space and leaving his meals untouched. Gone was the steeley-eyed entrepreneur. A portrait published in the Tulsa Daily World around this time shows an aged Brady looking weary and morose. In the early morning hours of August 29, 1925, Brady walked into his kitchen and sat down at the breakfast table. He propped a pillow in the nook of one arm, and rested his head upon it. With his right arm, he took a .44 caliber pistol, pointed it at his temple, and pulled the trigger. [28] Brady, who worked to divide Tulsa along racial lines, died a victim of his own curse.John Davis Brady. Student Photo, Central High School, 1921

THE BRADY DISTRICT TODAY

Today, the Brady Arts District is the focal point of multi-million dollar developments involving local organizations such as the George Kaiser Family Foundation, the Oklahoma Museum of Music and Popular Culture, the University of Tulsa, Gilcrease Museum, Philbrook Museum, and the Arts and Humanities Council of Tulsa. Local businesses also thrive in the district: numerous bars and restaurants, [29] the family-owned Cain’s Ballroom (which once served as Brady’s garage), and the Tulsa Violin Shop, to name a few. A large new ballpark separates the Brady district and the Greenwood area. [30] In 2005, the National Park Service/US Department of Interior published The Final 1921 Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey commissioned in 2003 by the Oklahoma Historical Society and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Memorial of Reconciliation Design Committee. The purpose was to determine if Greenwood possessed enough “extant resources” to merit national significance. The survey concluded that the Tulsa Race Riot is significant because it is “an outstanding example of a particular type of resource,” and “possesses exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the natural or cultural themes of our national heritage.” In addition to the findings, the report explained Brady’s role in segregating not only Tulsa, but Oklahoma. [31] Despite these findings, the Tulsa Race Riot area, including Greenwood, remains unregistered. Preservation consultant Cathy Ambler stated, in a February 2010 PLANiTULSA proposal: “Today, there is a faction of Tulsans who take issue with some of the associations and choices that Tate Brady was involved with, but there is no denying that he was a huge supporter of Tulsa and played a very big part in its early development.” In September 2010, the Brady Arts District was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, owing to its significance as a place of commerce. It enjoys the full benefits allotted under the designation. This article was originally published on Sept 1, 2011 Footnotes